|

In the spring Michalina was interviewed by a past classmate, Maya Broeke, on designing spaces for bees. Give it a read!

3 Comments

BC is home to over 450 species of native, wild bees. They contribute to pollination of our gardens, food crops, and wild ecosystems. Creating a bee garden is one of the best things you can do to support our native bees, since much of their habitat is being destroyed for human uses such as agriculture and housing. The main priorities of a pollinator garden are providing food and nesting sites for different types of bees.

Here are some guidelines to get you started on your own garden. Even keeping a few pots of bee-friendly flowers on your balcony will help the bees! Priorities in a Bee Garden 1. Plant native plants Native plants and native bees have co-evolved together. Native bees may not be able to access non-native flowers, so focus on native plants in a bee garden (although non-native plants and weeds can be incredibly important, too! See below) Heavily hybridized flowers often stop producing nectar and pollen making them useless for bees. 2. Don't use pesticides Never use pesticides on your garden. Insecticides and fungicides have been found to be extremely dangerous to bees. Ask the managers of wherever you buy your plants and seeds from if they use neonicitinoids. These insecticides infiltrate all parts of the plant, including nectar and pollen, and either kill the bees outright, or affect them sub-lethally by interfering with their learning and memory, reproduction, etc. This is becoming a very hot topic, with neonics recently being found to be dangerous to other wildlife too. Growing plants from seed or cuttings is a good way to avoid planting neonic plants. 3. Continuous flowering Plan your garden to have something flowering at all times. Bees need to eat every day, so try to provide flowers at all times of the season. Early and late flowering plants are especially beneficial. 4. Diversity of flower colours, shapes, and sizes Native bees are a diverse bunch! From large fuzzy bumblebees to tiny slick sweat bees, you can bet each type of bee will have its favourite type of flower. Cover your bases and plant a diverse array of flowers. 5. Plant large patches of a single flower It's easier for bees to forage if they can stick to a single species in an area. If you can't plant in large patches, don't fret, a single plant of one species if better than none! 6. Provide nest sites and materials Native bees nest in a variety of ways. Some like to live in holes in the ground, some nest in hollow stems, some in holes in wood, bumblebees will nest in abandoned rodent holes and birdhouses or at the base of ferns.... Ground nesting bees like bare, compact, undisturbed, well-draining soil in a variety of orientations from steeply sloping to flat. You can dig a pit and fill it with sand to create softer ground for bees, too. Plant grasses with hollow stems, and leave dead plants with hollow stems intact over the winter. Piles of hollow stems can be made to provide nesting areas. You can also make nests for solitary bees and bumblebees. Click here for more info from the Xerces Society. You can even make a insect hotel that is freestanding or mounted on a wall. 7. Providing water Provide a water container filled with rocks so the bees can climb down to the water easily. I have also observed bees drinking from moist soil and mud. Garden Management Strategies 8. Let the weeds live! Flowering weeds in the garden or lawn are great for bees! Clover, dandelions, etc. are fantastic. Let your lawn grow long, and let the weeds flower before you mow or pull them. 9. Leave vegetables to flower Let garden plants bolt and flower before pulling them out. Brassicas such as kale make especially nutritious pollen. The bees will thank you! Plant List Here is a list I have compiled from various sources that would be suitable for our area. Check out the resources below for more plant suggestions! Trees Maple Linden Fruit trees Nut trees Shrubs Nootka rose, Rosa nutkana Rhododendron Willow, Salix spp. (an important early bloomer) Elderberry, Sambucus spp. Black Twinberry California lilac, Ceanothus spp. Escallonia spp. Hardhack, Spirea douglasii Huckleberry Ocean spray, Holodiscus discolor Oregon Grape, Mahonia spp. (an important early bloomer) Red flowering currant, Ribes sanguineum Red Osier Dogwood Salal Salmonberry Saskatoon, Amelanchier alnifolia Shrubby veronica, Hebe pinguifolia 'Pagei’ Snowberry Thimbleberry Trailing blackberry Flowers/Herbs Under 30 cm Clover, white Clover, red and crimson Crocus spp. Dandelion Thyme, Thymus spp. (including creeping thyme) Sea blush, Plectritis congesta Sedum spp. Snow drops, Galanthus spp. Strawberry Thrift, Armeria maritima Flowers/Herbs Over 30 cm Alfalfa Alyssum spp. Aster spp. (e.g. Douglas aster) Basil Bee balm, Monarda spp. (especially lemon bee balm!) Bellflower, Campanula spp. Borage Calendula California poppy Catnip Chives, Allium schoenoprasum Cilantro Columbine, Aquilegia spp Comfrey Tickseed, Coreopsis spp. Cotoneaster spp. Cranesbill, Germanium macrorhizum, Geranium cantabrigiensis ‘Cambridge’ Douglas aster, Aster subspicatus Coneflower, Echinacea Blanket flower, Gaillardia spp. Fireweed Giant hyssop, Agastache spp. Goldenrod (contrary to popular belief, this plant does not cause allergies, but ragweed does) Heather, Calluna vulgaris Hollyhock, Alcea *Lavender Lupin, Lupinus Marshmallow, Malva spp Moldavian Dragon Head Pearly Everlasting Penstemon ‘mexicali’ Pieris japonica (important early bloomer) Purple toadflax, Linaria purpurea Rosemary Sainfoin Salvia spp. - Many are wonderful for bees! Sea holly, Eryngium maritimum Speedwell, Veronica spicata Sunflower Tall and short grasses (species tbd) Threadleaf phacelia, Phacelia linearis Verbena bonariensis Veronica Yarrow, Achillea millefolium Zinnia Fantastic Resources for Plants and General Bee Information Xerces Society Earthwise Society SFU Pollination Ecology Lab David Suzuki Foundation Book: Victory Gardens for Bees by Lori Weidenhammer (Vancouver local!) Check out these photos of other pollinator hotels around the world! Some are so cute and whimsical. You can also google "pollinator hotel" or "insect hotel" for some inspiring photos. Enjoy!

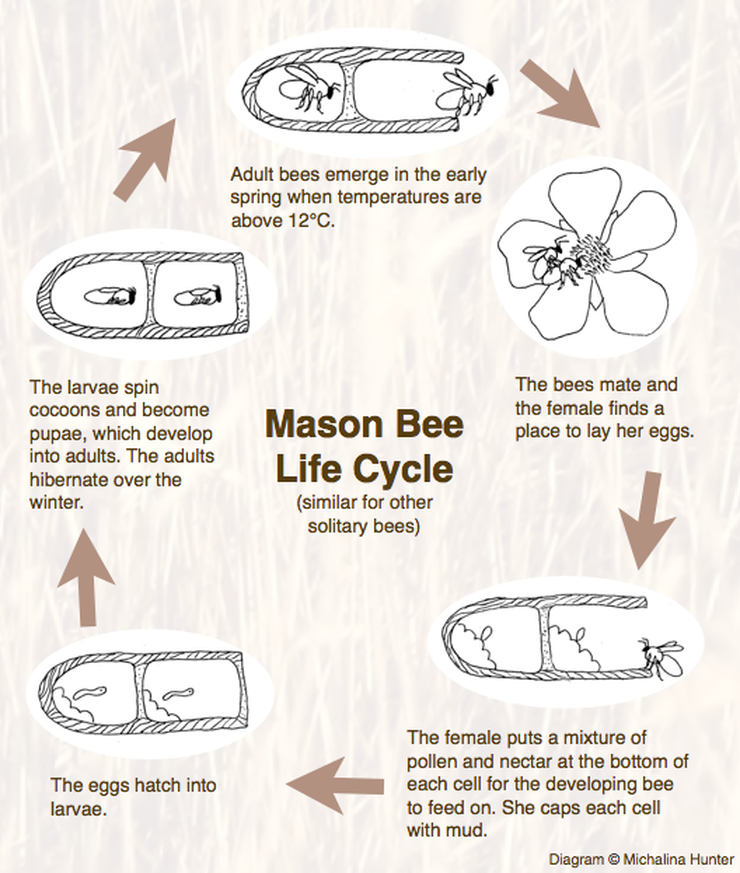

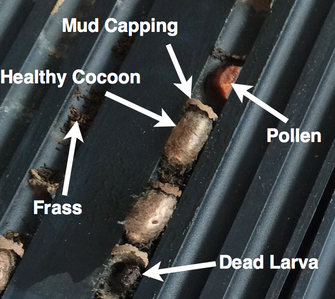

http://www.inspirationgreen.com/insect-habitats.html We've received many requests from people for more info on mason bee care. While we don't currently have live stream capabilities for sharing our in-person workshops, we can write how-to's! If you are local to Squamish or the Lower Mainland, stay tuned for more workshop dates in the spring and fall. We hope this post is helpful for keeping your mason bees happy and healthy. What are mason bees? Mason bees are a group of bees in the Osmia genus. There are 140 species in North America, about 60 in BC! They are solitary, meaning that they don't live in a colony with other bees (unlike honey bees which live in colonies of 50-100,000 individuals). Instead, the male and female mason bees live and work alone, except for mating. (See lifecycle diagram below.) Mason bee females may nest together in mason bee homes we provide them, but they don't really interact with each other. How to identify mason bees Mason bees are easy to miss- they look a lot like houseflies. They are usually dark and metallic blue/green around here, although they have longer bodies than houseflies and more distinct body segments (head, thorax, abdomen). Their bums are more rounded or "bullet-shaped" than other solitary bees that may look similar. A tip for telling flies apart from bees is flies have big bulgy eyes on the tops of their heads, while bee eyes are smaller and on the side of head (not counting honey bee drones). Flies have 2 wings, bees have 4. Another mason bee characteristic is they are only around in the spring- approximately from late February to June. The adults die after that. For that reason, they are great pollinators for early flowering crops, like fruit trees. The males are smaller than the females, have longer antennae, and often have fuzzy blonde moustaches- no joke!! The males can't sting, and while the females can sting, it's unlikely. How do I "keep" mason bees? Mason bees do not require extensive maintenance like honey bees. You can simply buy or make a mason bee home (lots of style options, but make sure you can take the whole home apart to access cocoons in the fall, or use paper tube liners in drilled holes), mount it outside in late February/March, and wait for wild mason bees to find it. They will get busy laying eggs in the home, and then it's your job to clean the home in August-October, and store the cocoons over the winter to keep them safe. Why do I need to clean the cocoons and mason bee home? In nature their cocoons wouldn't get cleaned! When we put up a mason bee home, we are encouraging the bees to lay a bunch of eggs very close together. In the wild, the bees would be forced to lay a few eggs over here in a hollow stem, and a few over somewhere else. With many nests together, it's easy for parasites to locate them and move from one nest tube to another. Your whole mason bee home could become a breeding ground for parasitic wasps, pollen mites, fungi, etc. over the winter (see photos below). So because we are setting up these unnatural situations, it's important for us to be responsible and give the bees a hand, so we don't do more harm than good. |

AuthorMichalina and Darwyn are beekeepers on Vancouver Island, BC, Canada. Archives

January 2018

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed