|

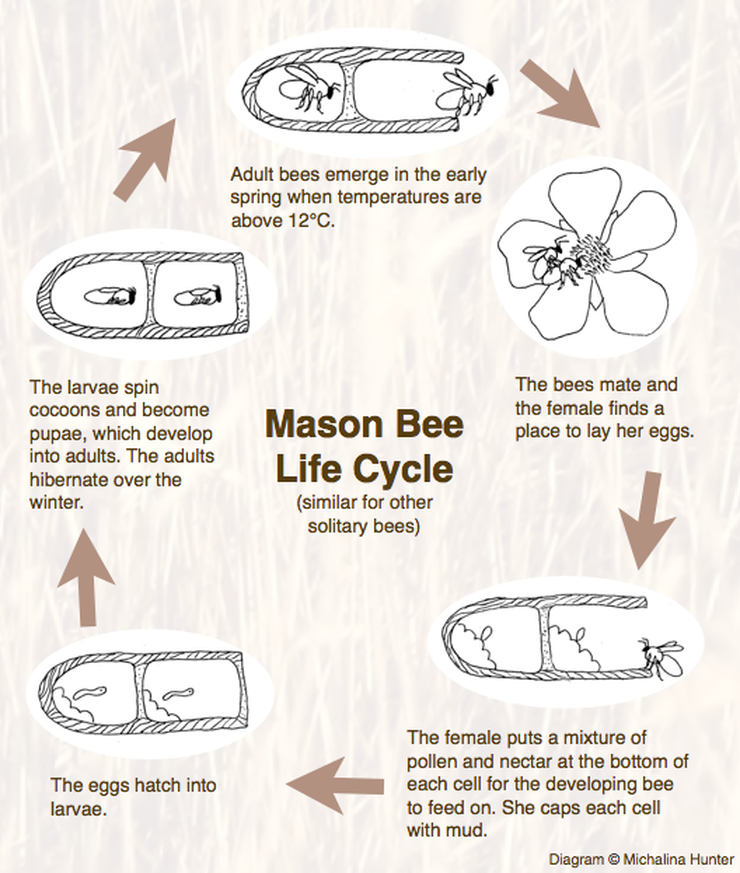

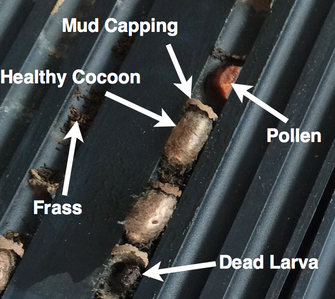

We've received many requests from people for more info on mason bee care. While we don't currently have live stream capabilities for sharing our in-person workshops, we can write how-to's! If you are local to Squamish or the Lower Mainland, stay tuned for more workshop dates in the spring and fall. We hope this post is helpful for keeping your mason bees happy and healthy. What are mason bees? Mason bees are a group of bees in the Osmia genus. There are 140 species in North America, about 60 in BC! They are solitary, meaning that they don't live in a colony with other bees (unlike honey bees which live in colonies of 50-100,000 individuals). Instead, the male and female mason bees live and work alone, except for mating. (See lifecycle diagram below.) Mason bee females may nest together in mason bee homes we provide them, but they don't really interact with each other. How to identify mason bees Mason bees are easy to miss- they look a lot like houseflies. They are usually dark and metallic blue/green around here, although they have longer bodies than houseflies and more distinct body segments (head, thorax, abdomen). Their bums are more rounded or "bullet-shaped" than other solitary bees that may look similar. A tip for telling flies apart from bees is flies have big bulgy eyes on the tops of their heads, while bee eyes are smaller and on the side of head (not counting honey bee drones). Flies have 2 wings, bees have 4. Another mason bee characteristic is they are only around in the spring- approximately from late February to June. The adults die after that. For that reason, they are great pollinators for early flowering crops, like fruit trees. The males are smaller than the females, have longer antennae, and often have fuzzy blonde moustaches- no joke!! The males can't sting, and while the females can sting, it's unlikely. How do I "keep" mason bees? Mason bees do not require extensive maintenance like honey bees. You can simply buy or make a mason bee home (lots of style options, but make sure you can take the whole home apart to access cocoons in the fall, or use paper tube liners in drilled holes), mount it outside in late February/March, and wait for wild mason bees to find it. They will get busy laying eggs in the home, and then it's your job to clean the home in August-October, and store the cocoons over the winter to keep them safe. Why do I need to clean the cocoons and mason bee home? In nature their cocoons wouldn't get cleaned! When we put up a mason bee home, we are encouraging the bees to lay a bunch of eggs very close together. In the wild, the bees would be forced to lay a few eggs over here in a hollow stem, and a few over somewhere else. With many nests together, it's easy for parasites to locate them and move from one nest tube to another. Your whole mason bee home could become a breeding ground for parasitic wasps, pollen mites, fungi, etc. over the winter (see photos below). So because we are setting up these unnatural situations, it's important for us to be responsible and give the bees a hand, so we don't do more harm than good.

19 Comments

|

AuthorMichalina and Darwyn are beekeepers on Vancouver Island, BC, Canada. Archives

January 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed